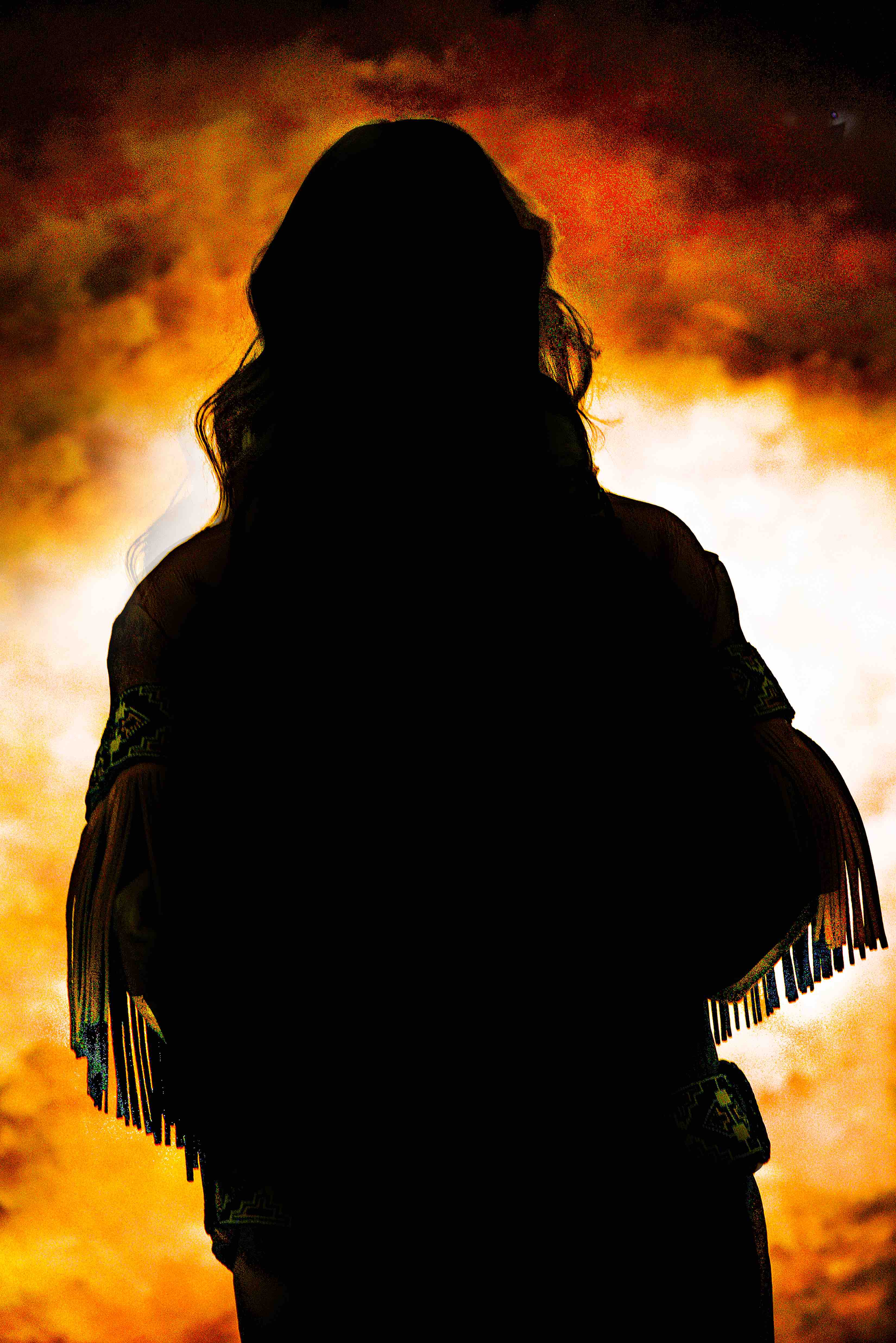

Jani Lauzon – Writer/Actor/Director/Musician/Puppeteer

I am writing this in response to an article written by Michelle Cyca in the Walrus.

Originally posted on FB on November 8th 2024.

This will be the first of a few posts.

I appreciate your patience as I contemplated my response to an article that appeared on the Walrus website, written by Michelle Cyca, focusing on my Indigenous identity along with the play I co-wrote called 1939. The week that it appeared was the final week of rehearsal for 1939, which I was directing at The Belfry Theatre in Victoria, so I was focused on supporting my cast in the leadup to opening. I followed that with time to grieve the loss of a very close friend of mine. My plan to post my public response on Monday was put on hold with the catastrophic loss of Murray Sinclair, especially since his question to us all, “What can we do to engage in reconciliation?” was one of the many things that influenced the writing of 1939. After two days in deep prayer, I finally have the capacity to address the Walrus article.

First, I want to acknowledge the upset this has caused. I feel such concern for all the collaborators of 1939 who have been affected. There has also been upset with regards to the process in this most recent production and I agree that better consultation with the local Indigenous community could have been achieved. For that, the community deserves an apology, and I offer one openly.

Second, and importantly, the Walrus article leads readers to believe that I have no Indigenous background, but to the contrary, my genetic testing shows Indigenous DNA. In their correspondence with me, Michelle and the fact checker indicated that they had access to my genealogy records and DNA testing (through what they called additional reporting) and that it did confirm Indigeneity but the story did not reflect this.

Earlier in my life, I was driven to find answers regarding my Indigenous ancestry as a result of my life experience: the negative treatment at Catholic school, the endless racist taunts on the playground, the time in the late 1980s while on tour that I was required to prepay for my meal and sit on the “Indian” side of a restaurant. At first, I tried to be my own genealogist, which in those pre-Internet days involved writing to churches and the government and spending hours at the archives in Ottawa going through microfilm. At one point, I was sure I had found the answers, and so I decided to take them to my father.

Shame in some families has led to family secrets, and this has been my personal experience. Until this point, when I had asked my father about our Indigenous ancestry, his response had been “maybe.” But when I shared my findings, he disclosed that his understanding was yes, on his mother’s side.

I brought my findings to one of the co-founders of the newly formed Métis Nation of Ontario who was a friend and colleague. He encouraged me to look deeper. I finally reached out to a genealogist, but because of my limited financial resources that process was limited in scope. She suggested DNA testing, which I pursued years later. My results confirmed I had Indigenous ancestry, but did not provide the instant family tree I was expecting. I am now engaged in a process of reaching out to relatives through 23andMe and have recently hired a genealogist who specializes in Indigenous ancestry.

The goal in writing 1939 was to engage in the TRC’s Call to Action #83 where Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists come together to create art that sparks conversation around reconciliation.

One concern we have encountered about this play is the use of humour while writing about Residential Schools. We chose to include it after much thought and consultation with our circle of advisors, who encouraged us to use it to demonstrate the resilience of the characters and to help the audience engage more deeply with the subject matter. We have been encouraged by the responses from Indigenous audiences in Stratford, Sudbury and Toronto, who have been thankful for that perspective and also for the opportunity to engage more fully in discussion during the “reflection space” offered by previous productions after each performance, many of which were led by Survivors or well-respected Indigenous facilitators.

I am aware that there are many excellent plays that represent the deeper side of the traumatic experiences that Indigenous children were forced to endure. Our focus was through a particular lens: the resilience, courage and creativity of five fictional Indigenous students. But we know that these characters represent only a fraction of the individual experiences of Survivors across this land.

In her article, Michelle Cyca writes that 1939 “at its core is Lauzon’s story—about her father and his experience of encountering Shakespeare at a residential school.” During the fact-checking process for the article, I had said that the story was only partially inspired by that. I was not asked to elaborate, so I will do so here. The play was mainly inspired by Yvette Nolan’s mother Helen Thundercloud. With Yvette’s approval we accessed a pre-recorded video interview where Helen shared her experience of how a very inspiring teacher taught her Shakespeare. That love was passed down to Yvette, greatly influencing her incredible legacy and expansive work in the arts today. That information can be found on The Belfry’s website.

When I was in my 30s, I learned that my father had attended KerMaria convent school and he gave me a copy of The Collected Works of Shakespeare that he had studied there. This was the main inspiration he provided, though I was influenced by his stories of his experiences as he was treated terribly by the nuns, priests and other students, leading to lifelong anxiety and low self-esteem. My father’s story differs from many in that he was not taken from his family but rather dropped off at KerMaria by his parents.

I believe Michelle concluded that the central inspiration was my father’s experience after referencing an online interview, where we were not discussing Helen’s influence nor the full details of the development process. She therefore was not privy to a great deal of context, including a multitude of workshops where we played Helen’s video for the actors; many discussions with Survivors; and talkbacks and reflection space conversations where this was made clear. Of far greater import than my father’s history was the experience of Bev Sellars as detailed in her book They Call Me Number One, which also informed a lot of the discussion around the development of this play. Indeed, Bev spoke at the Stratford Festival along with her husband, Bill Wilson, in the events surrounding the premier of the play. She also spoke to the entire team at The Belfry.

As for Shakespeare being taught in schools, we took some poetic license in the timeframe as to when Shakespeare was taught in the sanctioned schools, which may have had a different curriculum from that of the provincial and Church-run schools, which we believe may have been teaching Shakespeare earlier.

Another example of Shakespeare being taught comes from the Gernier High School, which was established in 1947 and was part of the Spanish Indian Residential School. In the Garnier Club Star student newspaper, Volume 10, No. 2, S. Panagowish reports “At present we are studying Macbeth, an ancient tragedy written by William Shakespeare. And the way this play goes, William must have really ‘skook a spear’. This subject composed of much figurative language requires real effort in order to understand what each character says.”

While 1939 is a story of family legacy, it is not of mine specifically. However, the research I did for this play led me to think more deeply about my father’s childhood experience and I found that KerMaria was included on a list of Residential Schools compiled by Aboriginal Affairs, which states that students at this school (and others) were ineligible for government compensation because it was solely funded by the Catholic Church. That list can be found here.

According to the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, “Residential Schools are defined as: [a] school system in Canada attended by Aboriginal students. This may include industrial schools, boarding schools, homes for students, hostels, billets, residential schools, residential schools with a majority of day students, or a combination of any of the above.”

Notably it states: “At the request of Survivors, this definition has evolved to include convents, day schools, mission schools, sanatoriums, and settlement camps.”

I encourage all who are interested in the bigger story to reference page 35 of Tanya Talaga’s new book The Knowing, where Murray Sinclair references this list and calls it Canada’s “dirty secret: 1,300 more schools that received no federal support – meaning they were solely financed by a religious denomination, privately run or provincial schools.” He continues: “Survivors have tried in vain to petition the government to add more schools to the acknowledged federal compensation list.”

In her article Michelle disputes this classification in opposition to the opinion of Murray Sinclair referenced above, saying the logic that students could apply to have their school on the list is backwards.

The research I have done reveals that many believe that the government wants us to know only about the sanctioned Residential Schools because it keeps the numbers of students affected lower. For me, in learning about my father’s experience, I have come to believe that far more children than we know of – than the government admits to – were victims of this system. This is represented artistically in 1939 by the growing number of children’s voices who sing The Maple Leaf Forever throughout the play.

In the Walrus article, Michelle says that I am a proponent of something called “body memory”. I am. However, I found Michelle’s writing about this process out of context and disrespectful of the artists who create using this methodology. Michelle references “this belief in a sort of mystical subconscious Indigeneity” without realizing that she is commenting on an internationally recognized process and the groundbreaking Indigenous artists who developed it. For example, the project she is referencing was one that I was working on with Monique Mojica. I have the utmost respect for Monique and her embodied practice along with her development of Indigenous dramaturgy. She is one of a few Indigenous artists to use an embodied practice in creative development. To me, Michelle’s comment dismisses this work without knowing its history and influence on hundreds of Indigenous artists.

Finally, I want to express my gratitude to all the collaborators in 1939. Please know that your work is important and your bravery deeply appreciated.

Jani Lauzon is a multidisciplinary artist of mixed settler and Indigenous ancestry. She is a 9 time Dora Mavor Moore nominated actress, a three time Juno nominated singer/songwriter, a Gemini Award winning puppeteer, an award winning director, and an artist educator. Her company Paper Canoe Projects was created to support production of her own work including: A Side of Dreams, I Call myself Princess, and Prophecy Fog. For more information on those shows please visit www.papercanoeprojects.com